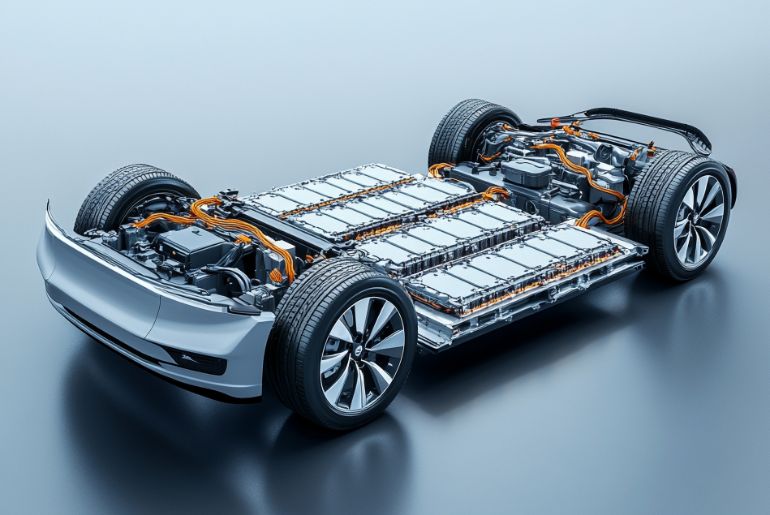

One simple factor makes the electrification of the global transport sector possible: the EV battery. As soon as the world transit from fossil fuels, the battery pack—usually one-third of a vehicle’s cost—curates an electric vehicle’s (EV’s) range, performance, and charging rate. Engineers have been searching for the optimal combination of energy density, power delivery, safety, and life span for many years. Now, there is one chemistry submerging today’s electric transportation. That dominant technology is the lithium-ion battery. This rechargeable powerhouse has effectively transformed the automotive landscape, moving from powering consumer electronics to supporting multi-tonne vehicles over long distances.

The popularity of lithium-ion (Li-ion) battery chemistry was not an accident; it emerged from a unique combination of performance characteristics. In short, they provide high gravimetric energy density, which is the amount of energy per unit of mass/weight, which occurs in most contemporary electric vehicle (EV) cells in a range of 150 to over 270 watt-hours/kg. That higher density matters because a lighter battery pack allows for more range and better overall vehicle efficiency. Compared to another standard chemistry, such as lead-acid or nickel-metal hydride, a Li-ion pack has outstanding performance characteristics for a smaller volume than those chemistries. Its success in the EV marketplace derives nearly entirely from the fact that it can be cycled many times with little, to no loss in capacity, offering longevity, reliability, and a long service life for vehicle owners.

The Architecture and Chemical Composition of Lithium-ion

A single lithium-ion cell is an impressive example of electrochemical engineering, which comprises four main components: a cathode (positive electrode), an anode (negative electrode), a separator, and an electrolyte. The magic happens with the lithium ions (Li⁺) moving in a reversible manner. During discharge (the EV is in use), lithium ions leave the anode and float through the electrolyte and separator to the cathode, while some electrons are permitted to pass through an external circuit to turn the motor. The process is reversed during charging because current from an external source pushes the lithium ions back from the cathode to be stored again in the anode.

The materials used in the electrodes define the particular performance characteristics of a lithium-ion battery. The anode often employs graphite for its role. The cathode uses various lithium compounds and determines the battery’s chemical classification. The most commonly used types in electric vehicles are Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (NMC) and Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminium Oxide (NCA), which are selected for their high energy density which means longer range. Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) is becoming more common due to its great safety, long cycle life, and lower cost due to not containing expensive cobalt, even if the energy density is a little less than a typical lithium-ion cell using NMC. Overall, an advanced Battery Management System (BMS) monitors the entire battery pack. The BMS is the ‘brain’ that monitors and regulates each lithium-ion cell from being overcharged or overheating. This is key for safety and longevity. All reliable lithium-ion systems have this smart monitoring.

Current Challenges and Optimizing Lithium-ion Performance

Despite being the dominant technology in the sector, the lithium-ion battery must overcome significant challenges before widespread acceptance of EV technology is possible. The major challenge is cost. The raw materials needed—especially lithium, nickel, and cobalt—have high costs and are influenced by geopolitical and supply chain considerations. Material costs is the primary reason why EVs are still more expensive compared to comparable ICE vehicles. In addition, relying on these critical materials raises significant environmental and ethical issues regarding extraction. Reducing reliance on expensive materials is a main goal for all major lithium-ion manufacturers.

A significant challenge revolves around optimizing performance. For many consumers, charging time and range anxiety are still significant barriers. While battery technology has increased the energy density of lithium-ion batteries, which extends driving range, rapid charging heats the battery, which can accelerate the degradation of battery components, decreasing overall lifespan and capacity. Engineers are continually trying to improve the thermal management system (cooling system) that protects the lithium-ion cells. The current cycle life of high-quality lithium-ion EV batteries—often exceeding thousands of cycles—is usually well beyond the vehicle’s stated life, but consumers are always looking for more. Improvements to the anode materials, such as incorporating silicon into the graphite anode, are already being implemented to further improve energy density within the existing lithium-ion framework. Lithium-ion designs continue to be an area of improvement and outperform rival technologies. The goal remains to build a lithium-ion battery pack that is stronger, cheaper, and safer.

The Future of the EV Battery Ecosystem

Looking ahead, the EV battery landscape suggests changes and a degree of diversification, but the lithium-ion chemistry will remain the mainstay. Solid state batteries represent the next generation technology that is anticipated as the most promising—this technology replaces the flammable liquid electrolyte of conventional lithium-ion batteries with a solid electrolyte/separator material. Solid-state technology promises a significantly higher energy density (potentially up to 500 Wh/kg), faster charging, and fundamentally better safety due to the elimination of the liquid component. While commercialisation is still a few years away, it represents a potential evolution of the existing lithium-ion chemistry, often still using lithium metal for the anode.

Parallel to solid-state development, entirely new chemistries are being explored, primarily driven by sustainability and cost. Sodium-ion batteries (Na-ion) represent an increasingly viable alternative to lithium ion for applications such as small vehicles and stationary storage applications. Sodium is far more abundant and a lower-cost metal than lithium, and Na-ion batteries will be manufactured in the same plants that are now making lithium ion packs, making them readily scalable. Na-ion batteries will have a less energy density than high-performance lithium ion batteries, but the cost and safety features are a big plus. There are some other competitors, including lithium-sulfur and zinc-ion, which are also currently being developed, each representing a different trade-off between energy density and cost.

It is crucial to address the recycling of EV batteries for the sustainability of the ecosystem. Given the high costs of raw materials, especially lithium, nickel and cobalt, recycling is a necessary aspect of economics. Governments and industry stakeholders are making a large investment in establishing closed-loop recycling systems to recover materials from disposed lithium-ion batteries. This reduces the need for resources to be mined new, and will help create a real circular economy for the leading lithium-ion energy source. This move toward greater sustainability will ensure the lithium-ion technology—and its successors—continues to power the world’s transition to electric mobility. The continued refinement of the lithium-ion cell and its eventual evolution will define the success of the electric vehicle revolution.